“Infinite diversity in infinite combinations.” That is one of Star Trek’s most prominent mottos (even if it was ultimately created out of a desire to sell merchandise). That is what the spirit of Trek is meant to embody. The wonder of the universe wrapped up in a statement of inspiration and acceptance, a promise to pursue that which we do not understand; to embrace it with optimism and open minds.

They are captivating words that Star Trek has worked hard to advocate, with varying results. But if Trek intends to be relevant long into the 21st century, those words could use re-examination. Showrunner Bryan Fuller has promised a return to this idea, this motto, in his new show Star Trek: Discovery, and some vague (but heartening) promises have been made in that direction. Still, the question stands: in this day and age, how can Star Trek renew its commitment to infinite diversity? What should this bright, shining future show us fifty years after its inception?

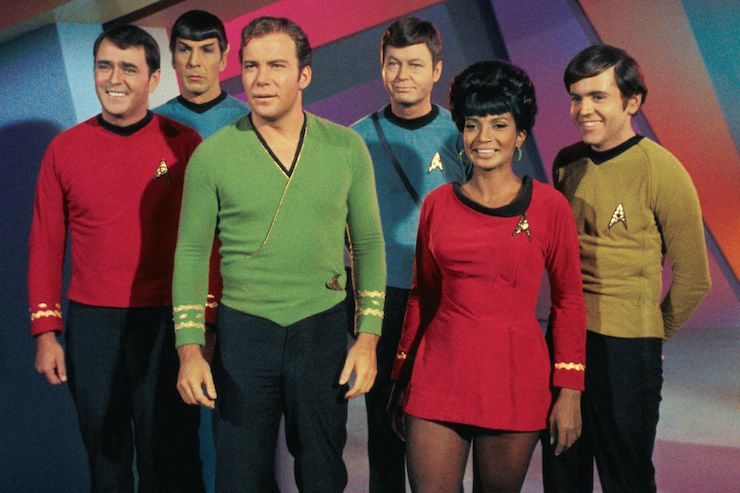

Star Trek been held up as an example to aspire towards since its creation. The performers, writers, producers, and directors involved have long understood the impact of what they were helping to build. Actors to astronauts have cited Trek as the reason that they believed there were no limits to what they could achieve. It is a legacy that Star Trek fans are rightly proud to be a part of.

But Star Trek hasn’t always been a perfect embodiment of these ideals. Though it was quite progressive for its initial audience fifty years previous, the Original Series is painfully tame by current standards. That’s down to the passage of time—what seemed progressive in 1966 was old hat during Trek’s resurgence in the 1990s, and in turn what seemed progressive then is behind what seems forward-thinking now—but there are many areas where Trek never quite bothered to push the envelope. Up until the present moment, certain topics have been seemingly off-limits on Star Trek: discussions of human faith, of gender and sexuality, of deeply rooted prejudices that we are still working through every single day as a species, and more.

If Star Trek wants to continue its mission to elevate us, to showcase the best of our humanity and what we can achieve, it needs to be prepared to push more boundaries, to further challenge assumptions, to make people uncomfortable. And doing so in an era where viewers can instantly—and loudly—share their opinions will undoubtedly make that even harder than it used to be. But without a willingness to be a part of the present-day cultural conversation, Star Trek loses its relevance, and its legacy stops here.

There’s a lot left for Star Trek to explore, so where can the series go in its next 50 years? Here are just a few ideas to keep in mind.

LGBT+ is More Than Just the LGB

Bryan Fuller has already enthusiastically stated that Discovery will have a gay crew member. This excited many fans who have been pushing for better queer representation in Trek for decades, and is undoubtedly exciting for Fuller as well; when he made the announcement, he added that he still has a folder full of hate mail that the writers received during the run of Star Trek: Voyager, when rumors spread that Seven of Nine was going to be a lesbian. As a gay man, it is understandable that Fuller is eager to have final word in the argument of whether or not Trek’s future has a place for queer people.

Problem is, western culture has moved beyond that question in the past couple of decades. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual characters are a consistent part of mainstream entertainment now (especially in television), and have been visible in that arena for quite a while; a fact that Fuller himself is aware of, as he cited Will and Grace as the point of “sea change.” Helmsman Hikaru Sulu was depicted as a gay (or possibly bi) man with a family in Star Trek: Beyond. Granted, it’s true that despite the headway, queer characters are frequently mistreated in fiction, mired in stereotypes and then murdered just for daring to exist. But it doesn’t change the fact that, at this point in time and after such a storied history, having a gay crew member on the Discovery is the absolute least that Star Trek could do. It’s the bare minimum, a temporary patch on something that should have been fixed long ago.

What about the rest of that alphabet? Where are the asexuals in Trek? The trans and non-binary folks? Intersex people? What about the people who practice polyamory? Sure, we had Doctor Phlox on Enterprise, but he was an alien whose entire species practiced polyamory, thereby preventing any exploration of an example on the human front. (Having Phlox encounter a human who also practiced polyamory would have been a fascinating opportunity to compare and contrast, and would have also prevented polyamory from being put down to “an alien thing.”) Moreover, we never encounter his culture in any meaningful way to see how that polyamory functions in practice. So how do we examine and internalize these differences? If the answer is “well that was handled in one episode on TNG via another species”, that answer is not good enough anymore. These groups are full of people being maligned and ignored, and for many of them, that ignorance is costing lives. Having a gay crew member in Discovery will be wonderful, but there are still so many people who deserve to be represented in the future Trek creates.

Disabilities Don’t Need to Be “Cured”

Seeing Geordi LaForge on Star Trek: The Next Generation was a big deal over twenty years ago. Trek had depicted blindness before on the Original Series (in the episode “Is There in Truth No Beauty?”) but having a main character in a television series with such a clear disability was just as rare then as it is today. What’s more, Geordi was never defined solely by that disability, and had one of the most important jobs on the Enterprise (D and E!). All of these things were groundbreaking. The only thing was, due to his VISOR, Geordi could effectively see (in some ways even better than your average human).

To a certain extent, this makes sense. Star Trek occurs in the future, and medicine has leapt ahead by centuries. Its limits are defined by technology and morality rather than economy. More to the point, even now doctors and scientists are coming up with ways to fix issues in ways that were once unthinkable, transplanting organs, limbs, and even faces, and making rapid progress in creating controllable and flexible artificial limbs. (Perhaps it would make more sense to see Starfleet officers who look like the Borg, with cybernetic implants and robotic limbs aplenty.)

But as some diseases are cured, new ones always arise. And Trek has a strange track record in that regard, as it often runs the gamut between extremes when it comes to health and wellness; either you have a problem that can be easily amended with the use of tech and/or the right medicine, or you have a debilitating disease that is going to kill you. There is very little in-between. As a result, we find few characters living with disabilities in Trek. And the exceptions—such as Melora in her eponymous DS9 episode—frequently leave something to be desired, as they rely on the “medical model” of disability; meaning the idea of disability as something that should be solved or cured. Not only is this unhelpful in a broader sense, but it ignores the value of disabled lives by making it seem as though people who have disabilities are inherently missing out because they are not traditionally able-bodied.

If Star Trek were to key into the “social model” of handling disability, then we would see people with various disabilities—both mental and physical ones—working side by side with non-disabled friends and shipmates. Accessibility would be built into starship design, considerations made in prepping for away missions, text rendered in different fonts for officers with dyslexia, and so forth. We would see people with disabilities simply living their lives, and take that concept to heart going forward.

Focus On Current Issues

This is basically a given, but as Star Trek was a response to the politics and issues of its time, new incarnations must look to the current landscape and comment on the problems we now face. Nichelle Nichols has famously told and retold the story of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. asking her not to leave the role of Uhura midway through Star Trek’s original series run, due to how important her presence was in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement. Having Pavel Chekov on the bridge during the Cold War was a deliberate move on Gene Roddenberry’s part to suggest that peace would triumph. The Cardassian occupation of Bajor detailed in DS9 brought issues of terrorism and the lives of refugees to the fore at a time when the Oslo Accords had just been signed. Star Trek has always looked to the here and now, and used our current conflicts as an example to promote hope rather than fear.

Nicholas Meyer thankfully gave confirmation of that same intent during the Star Trek: Discovery panel at Mission New York, saying that commentating on present events is built into Star Trek (and then citing how the end of the Cold War was a springboard for the plot of Star Trek VI). Given the wealth of social, political, and environmental strife in the world, it shouldn’t prove any difficulty to find material for a Star Trek series today.

Complexities of Faith

Star Trek has worked hard over the years to offer detailed and fascinating faith systems for many of the aliens encountered by the franchise, including the Klingons and the Bajorans. But when it comes to humanity… there’s an odd absence. Some of this comes down to creator Gene Roddenberry being an avid atheist—he explicitly prevented stories about religion from being told while he was running the show, and whenever the Original Series encountered gods, they inevitably proved to be false. To whit, there’s an infamous treatment for the Star Trek motion picture where Roddenberry had Captain Kirk fighting Jesus.

But faith, in one form or another, is a long-standing part of humanity, in many ways irrevocably intertwined with culture. While some aspects of religion have divided humanity over time, faith can be truly beautiful and uplifting, and is needed by many as a source of comfort and community. And at a point in time where religions themselves often get demonized in place of the radical groups purporting to endorse them, showing these faiths alive and well in Star Trek would be a remarkable gesture. Religion is still often a cause for conflict among humans, but here there lies an opportunity to show how faith can create connections between people, and perhaps create dialogues between humanity and other alien races. Showing characters who live so far in the future engaging with faith in the interest of exploration and friendship is an example that humanity could use.

Faith as a construct is arguably as central to humanity as aspects that we cannot control, such as sexuality or ethnicity, and does not always apply to us in a religious sense; faith informs a large part of our various worldviews, regardless of whether or not it is attached to a deity or system. Without an acknowledgement of that, Trek’s vision of human beings is incomplete.

Handling All Forms of Prejudice

The initial concept of Star Trek was meant to show (during the height of the Cold War, no less) that humanity would not disappear in a nuclear winter. We would survive, learn from our mistakes, thrive, and work together toward a better future. When Star Trek tackled themes of prejudice, it typically used an alien scapegoat rather than a human one—the xenophobic terrorist organization Terra Prime, Picard’s fear of the Borg after his experience being assimilated, or the ways in which members of various Enterprise crews showed disdain and bigotry toward Spock and T’Pol. The idea was to suggest that humanity had gotten past the issue of internalized prejudice where its own species was concerned, yet still directed that impulse outward from time to time.

But by acknowledging that those prejudices still exist—even if they are focused primarily on Vulcans or Klingons—it becomes impossible to suggest that humans won’t ever aim those prejudices at other humans again. The spirit of Star Trek is not about humanity advancing to the point of perfection, it is about us striving for a better ideal. Which means that Trek must continue to show people making mistakes on account of internalized biases and learning from those mistakes. The utopian leanings of Star Trek are not due to a lack of conflict—they are due to people being enlightened enough to own up to their own shortcomings, to consider other perspectives, to work harder in the future.

All of this means that Trek must continue to acknowledge and display prejudice, between humans as well as alien cultures, and then set the bar when it comes to handling that conflict and moving past it. This was something that Deep Space Nine excelled at in particular, but doing the same on a Starfleet vessel will create a different atmosphere. The chance to explore the true difficulties of existing side-by-side on a starship with several hundred of the same faces for years on end will receive the consideration it deserves.

With all this in mind, where does that leave Star Trek’s luminary future? With us.

Star Trek is optimistic at its core, and loves to ruminate on what makes humanity so wonderful, often presenting us with a myriad of examples that other characters are meant to take to heart—Spock, Data, and Seven were constantly learning about what made humans unique and formidable as a species. And the answer Trek gives us is typically: we’re incredible because we’re imperfect. We are passionate, we blunder through, we are messy. It’s a good lesson to be sure, and a comforting take on human nature.

But what if there is more to us than that?

“Infinite diversity in infinite combinations.” These words are a cornerstone of Vulcan philosophy, but they are pointedly an apt description of the entire human race. The spirit of Star Trek is exploration, and the universe it resides in posits that humans will be the natural ambassadors of the Federation’s message of unity and discovery. That we are poised to enter the galaxy with our arms outstretched, and that others will want to join us. Based on what, though? Our charm, our creativity, our business acumen? Let us hope not. Let us hope instead that it is because we are so intricate as a species—so infinitely diverse—that we are perfectly equipped to handle what’s out there. That is the bright future we’re looking for. A point somewhere in the not-too-distant future when we are so interested in understanding each other’s differences, in honoring and respecting one another, that it is only natural for us to extend that exploratory spirit outward.

Fifty years later, it’s the only ongoing mission that truly matters. And it’s one that Star Trek—with any luck—will always uphold.

Emmet Asher-Perrin is a staff writer with Tor.com. You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.

“faith, in one form or another, is a long-standing part of humanity”.

Thank you for this. Too often in science fiction human faith is either ignored or laughed at. I for one would love to see a practicing Christian on the show, not to shove it down our throat, but because it is a part of many people’s lives and should be acknowledged. If they really want to be unsubtle about it, they could have a Christian and a Muslim on the ship discuss the differences in their faiths and marvel at how humanity in the past killed over such differences.

Just to show there’s more than one way of looking at things, I always see fictional futures without religion as a hopeful prediction of humanity’s evolution.

To echo the sentiment in #2, Star Trek has always had a vision of humanity’s future that saw all the major fault lines in our society (gender, ethnicity, nationality, religion) fade as we came to think of ourselves as one species within a larger community.

Even though most of the series gloss over it, the economy is radically different as well, with little talk of money unless Starfleet members were doing business with members of non-Federation species.

That said, I watch Star Trek because I like the different situations the crew finds themselves in, the places they visit, and some of the problems they have to solve. I don’t want the show to become overly concerned with the personal lives or identity issues of the characters.

What need do we have of religion when we can touch the stars?

A thing I noticed while watching TNG: the episodic nature means that the plot where Worf was temporarily paralyzed and had to re-learn how to walk after undergoing a surgery to regain his mobility effectively got swept under the rug by the rest of the series. Which is a shame, because there is a subset of the population who do abruptly lose mobility due to an accident or illness and then have to adjust their lives accordingly. It would have been nice to have more opportunities to represent that, instead of having it all packed into an episode-long plot about assisted suicide that was resolved by pointing out that there was a surgical procedure which could give Worf his mobility back. More screen time usually means more nuance.

@1:

Yes. If nothing else, I’d like a glimpse at a multi-faith community on a starship. Sure, we’d like a future that doesn’t implicitly uphold one faith as the gold standard (Hi, season 3 TOS, you’re not fooling anyone with your roman planet,) but there’s still got to be room for people to practice their religion. As we’ve been seeing in France, a secular government that discourages parts of it’s population from expressing their religion isn’t the answer.

And the best way to do this is to have multiple religious characters that are of different religions, along with a subset of atheists. If nothing else, it could make for a great holiday episode.

@2: My perspective is that it depends on whether that lack of religion seems enforced, (by the author or society) or if it seems like it just never came up because it isn’t relevant to the particular characters we’re focusing on. Worlds where there isn’t any one religion that primarily influences society, but you can assume that individuals are free to practice, even if the main characters don’t, seem a lot more hopeful to me than ones where the author seems to believe that actively eradicating religion will solve the woes of the world, because those ones strike me as throwing the baby out with the bathwater. And sometimes there’s the implication of the western world having forced complete secularism on everyone else, which is pretty gross to propose as a solution or a route to utopia.

Now, in Star Trek’s model, where they’ve supposedly solved world hunger and resource shortages, there’s not a lot of need for religious institutions as societal safety nets for the poor and disenfranchised, but they can still be used to foster a sense of community… though obviously there’s room for religion to change with the times. In fact, many would need to in order to fit into later centuries without causing friction. Just as an example, because I was raised Catholic and am more familiar with it – overt acceptance of transgender and gender non-conforming people would have to become doctrine at some point. And that would probably have to get addressed during the show in order to prevent the audience from taking away the message that nothing has changed since now.

Exploration of “Faith” is best left to the Kai Winn model. Explore all the ways it stifled us, held us back, lead to obscene abuses and tortures, and why it is a bunch of superstition that we all need to leave behind as we move forward. Religion is the backwards path.

I always thought that Humans are intentionally kept bland in Star Trek so that the interesting ideas can be used to differentiate the various aliens they find. Take Dax for example: is there any reason ST humans could not duplicate that effect and have a linear sharing of memories between individuals? I die, here is the flash drive with my memories, plug it into your head?

Expanding humanity on Star Trek means to expand what is bland. Black female communication officer? Boring. Russian navigation officer? Boring. Gay helmsman? Boring. And so we make progress.

I’m in full agreement with Halien (#3 above).

I’ll even take this a step further, with no disrespect intended to Emily – I think that the worst thing the Star Trek franchise can do in the future is become a “check the box” attempt to appeal to every cause out there, which appears to be what this article is advocating. Star Trek and Sci-Fi in general work best when there is a lively and interesting story, and these types of characters, situations, and belief systems can not only be worked in logically but, most importantly, they are introduced in such a way as to support and strengthen the story. When Sci-Fi (and any other form of popular entertainment) stops being about the story, and becomes about finding a way to write a story to fit all the types of things mentioned in this article, it has no chance of being successful. While this may not be a concern to many on the more activist side, the logical impact of this is that the power of the stories to make change happen is totally lost.

I would love to see a Star Trek that spring boards off what DS9 did and tried to do. DS9 is the most “Adult” Star Trek show. It made arguments about the nature of war and how far we can legitimately go to preserve our way of life without crossing over the line and making a mockery of our core values. It dealt with religious issues with the Bajoran Faith and how Sisko was the “Emissary of the Prophets” and was very uncomfortable with that role but slowly and painfully learned to embrace it. It dealt with issues like the Aftermath of War and Occupation and how some communities are shafted by the powers that be, i.e. the border communities between the Federation and Cardissa after the Cardassian War. It tried to deal with some of the burgeoning questions that where starting to filter into the mainstream about the nature of human sexuality. It dealt with prejudice, particularly the way that the Cardassians looked down on everyone else and how the Ferengi where portrayed. In closing I want to see a Star Trek that goes back to it’s Core Mission Statement of both entertaining us while also holding up a mirror to the issues we are grappling with as a species today. I love authors like Charles Dickens and shows like the Twilight Zone because they do both of these. You do not need to dumb down something to make it appeal to a broad spectrum of people. You just have to got about it smartly. Finally Star Trek for me has always been about having at least one show on the air that is willing to push buttons with it’s viewership and make them think. I really hope this new show will do this.

.

Going out of the way to include characters of various sexualities and religions is fine, but in the Star Trek universe there is no story there. Humanity has reached the point where no one bothers to fight about these characteristics. Having everyone sitting around being accepting of other characters’ personal lives would not be very dramatic. Or worse, they could fall into the way first season Picard was always commenting on how advanced they all are compared to the shitty humans from the 1980s.

Religion isn’t the backwards path. People who say that are judging faith based on the actions of bad people. Faith fulfills the human need for something beyond material life, provides a philosophical framework that encourages doing good toward our fellows, and encourages a kind of introspection that results in self-improvement. The truth is that we don’t know everything. We can’t. As long as we don’t know what’s on the other side of death, we’ll keep speculating, wondering, and comforting ourselves with differing views of what is to come. In that way, faith is permanent. So there should certainly be depictions of faith within Starfleet.

I think Captain Picard sums up my thoughts best when he responds to Data’s question about what he believes happens after death.

“Considering the marvelous complexity of the universe, its… clockwork perfection, its balances of this against that, matter, energy, gravitation, time, dimension; I believe that our existence must be more than either of these philosophies. That what we are goes beyond Euclidean or other practical measuring systems, and that our existence is part of a reality beyond what we understand now as reality.”

@11 Very well put. Picard meditates further on time, life, death and meaningfulness in this quotation from STAR TREK: GENERATIONS:

“Someone once told me that time was a predator that stalked us all our lives. But I rather think that time is a companion who goes with us on the journey and reminds us to cherish every moment because they’ll never come again. What we leave behind is not as important as how we’ve lived. After all, Number One, we’re only mortal.”

Excellent article!

@10/Theo16: Having characters who are accepting of each other doesn’t eliminate the potential for drama, or stories. One of the things I love about the original Star Trek is that the main characters are close friends who look out for each other, and they have quite dramatic adventures nonetheless.

A bit odd to see some Star Trek fans look down on religion when the fandom, and fandoms in general, often fill the role of religions. Is that scripture or a Spock quote on your wall? Is that a passion play or a cosplay event you’re attending? If not, then thank the Great Bird you’ve never had to consider “canon” or witnessed different sects getting into heated arguments about various interpretations of “His Vision.” Yes, live long and prosper, give the Vulcan salute, diversity is on your side. No religion needed.

#11 That is why we have science, not faith. To wonder at the unknown and determine to make it known. Faith (even of the heart) is to take things on trust and accept the unknown as unknowable. That is something to be put behind us, we do not have the luxury nor the need to call something unknowable and not work to make it known.

Besides, we already know what is on the other side of death. Nothing. This is all there is. Death is the brain shutting down, and once that shuts down so do we. That is it. Anything else is fanciful wish fulfillment. Religions only claim there is something else in order to make their followers happy in their status quo and not demand something more in this life. That is something none of us should accept. We get one life, this is it, when we die all that we are ends and only what we have done remains.

I sure hope Star Trek never becomes fanciful wish fulfillment.

I want a running joke where Muslim science officer and Episcopalian doctor are constantly interrupted while having theological arguments. Even better if there’s a Jewish character to side-eye them about overthinking it.

I’ve read a fair amount on Star Trek’s approach to religion (including the books Religions of Star Trek and Star Trek and Sacred Ground), and I agree that the depiction of a religion-free humanity is problematic. After Roddenberry’s death, the TV series were able to deal with religion and faith more seriously. As Michael Reddy says @9, Deep Space Nine dealt with religion via the Bajoran religion; there was a fine episode, for example, on the conflict over teaching that the wormhole was a fulfillment of prophecy in the school on the space station. Voyager also respected Chakotay’s non-culturally-specific Native American spirituality and had at least one episode (“Sacred Ground”) which left open a door to a reality that can be accessed only through faith (though I don’t agree that science and faith are at odds in the way that episode implied). There were two major ways, though, in which the various series did not represent the complexity of religious experience and practice accurately and fully.

First, any alien culture that had a visible religion or spiritual practice (e.g. Vulcan meditation-like practices) had only one such religion which characterized the whole alien race. Why don’t other planets/races have a mix of cultures, including a mix of religious traditions? Not only that, there was generally a single religious interpretation that held sway in any alien culture that had a visible religion. In the episode of DS9 I just referred to, there was *a* Bajoran religious interpretation of the wormhole. Now, really. Wouldn’t there be a huge range of Bajoran religious interpretations of the prophecy, and the sense in which the wormhole could be viewed as a fulfillment of prophecy? People who interpreted it more “literally” and people who interpreted it (still within the framework of Bajoran belief) more metaphorically?

Second, religious or spiritual worldviews were generally race-specific. True, Sisko gets caught up in the Bajoran religious worldview in his role as Emissary of the Prophets, which he ends up accepting. Nonetheless, in general everybody’s religion seems to apply only to their own culture/race. There is a Klingon afterlife, but it apparently only applies to Klingons. Perhaps this is thought to allow people to get along? But it’s not accurate to how religious worldviews work. These are attempts to symbolize What Really Matters and What It’s All About which take account of the entire universe, to the extent that the religious culture is aware of the universe. So, yes, there might be attempts to “convert” people of other races. But more to the point, the religions themselves would struggle with the Big Questions as they apply to all those other sentient creatures we’re interacting with. That means that there would be religious thinkers who would be ALL EXCITED about listening to and talking with thinkers of alien religious traditions, to find out what insights we have come upon in common and what we can learn from each other. These conversations apparently never happen in the Star Trek universe. These conversations are happening all the time among religious humans deeply immersed in their respective religious traditions, conversations where people are eager to learn from each other and thereby develop their own religious thinking into more complex and rich forms. IDIC.

I am a progressive/liberal, strongly feminist, science fiction-loving, theological scholar and churchgoing Christian. As for the idea that religion is the impetus for much evil: well, yes, religions are human worldviews about What Really Matters, and human worldviews about What Really Matters, when they are absolutized and allied with human power structures, have inspired countless horrors. A few of those absolutized human worldviews have been atheistic, many have been religious. That aspect of human religiosity, however, is not the whole story of human religion as communally transmitted faith and spiritual practice.

@5 Quill–very good point, about the limits imposed by episodic storytelling. Perhaps the fact that Star Trek: Discovery will have story arcs extending over many episodes will allow it to tell just such a story about developing and coming to terms with a significant disability (which is not cured by all-powerful magical future medical tech). Also, about everyone around the person coming to terms with the change.

@19 Saavik

Some of the reasons for only representing a single religion per culture have to do with the limitations of the format and the episodic nature of most Star Trek series. In reality, many planets probably would have several different theologies. But it’s very possible that alien civilizations could have ended up with one dominant or official faith too.

You said that religions are human worldviews about What Really Matters, but they’re only one possibility. Philosophy offers a variety of non-religious options too.

I’m currently reading Ara Norenzayan’s book, Big Gods, about the social advantages offered by the religions that came to dominate our world. She has good insights, but she also points out that in the Western world, the emergence of secular, largely atheist states shows that you don’t need religion to provide social cohesion and cooperation if there are strong governmental/civil institutions and rule of law in its place. This strikes me as the vision that Star Trek has for humanity, that this kind of thinking gradually replaces religion, as it has in several parts of Europe.

In my mind, that’s a positive development, and one that shows religion may not be humanity’s only choice.

I remember a throwaway line in one of the S.C.E. books about debating when religious holidays ought to be observed, because stardates didn’t match up with any recurring Terran religious calendar, not to mention calendars on other planets. Although the Enterprise-D had ‘Captain Picard Day’, we have no idea if that was a repeat holiday or a one-off, and I don’t recall anyone celebrating birthdays, for example, in the Star Trek universe.

@21 Halien, Yes, indeed, there are non-religious human worldviews about What Really Matters. I didn’t say *all* human worldviews about What Really Matters are religious–in fact, in my last paragraph I mentioned atheistic worldviews. That was in a negative context, but I do not mean to say that atheistic or nonreligious worldviews are a negative force in human cultures. Certainly nonreligious and atheistic worldviews can be positive. Even the definition of what makes a worldview “religious” is a very complicated question, with different human cultures having different assumptions about what makes a religious way of being or thinking religious.

I do not think that as a species we will evolve beyond religion and faith, but I think that one can make a rational argument for that outcome–and, of course, one can hope that that will happen, as Roddenberry did. I tend to see the shift into secularism in Western Europe (and, increasingly, in the USA) as consequent to the postmodern move from communally-based identity to individualism. That’s related to what you say about the diminishing need for religion’s binding force, but it’s as much about pluralism eroding organic community as it is about the establishment of a secular rule of law. My sense is that pluralism erodes organic community even where a secular rule of law is not firmly established. (By the way, when I talk about pluralism eroding organic community, I don’t mean to say that’s a bad thing! There’s loss, and there’s much gain. IDIC!)

Saavik @19: “Why don’t other planets/races have a mix of cultures, including a mix of religious traditions?”

Bear in mind that other planets generally only have one *pub*.

@22 The Mad Librarian: traditional human holidays in Star Trek are a very interesting issue. That’s another way of looking at how Star Trek deals with human multicultural inheritance and communal memory. Here are the trad human holidays in ST that I know of:

TOS–“Charlie X”–there’s a special meal for Thanksgiving!! So, one North American traditional holiday that got observed in Starfleet.

TOS–“Dagger of the Mind”–Kirk and Helen Noel (in the past) at and after a Christmas party

ST:Generations–Picard celebrates Christmas with his imaginary family in the Nexus

But yes, there are birthdays: Kirk has had birthday parties in two movies now, right?

It is amazing when a atheist writes something that seems to indicate that he thinks his belief system is immune from violent fanaticism while in the same paragraph expressing an eliminationist fantasy against the religious.

@26 Crusader75

As someone who leans atheist, I find it a little confusing when someone refers to atheism as a belief system. There are political ideologies that include atheism and view religious institutions as competitors, but your garden variety atheist usually isn’t a subscriber. For people like me, values aren’t derived from a religious system because I don’t find the moral, factual, and mythological ‘truths’ claimed by most religions to be plausible.

Christopher Hitchens pointed out that most people come by their religion by being born into a family or community of believers. That says to me that religion operates as inherited tradition that doesn’t come in for as much scrutiny as other types of information we are asked to evaluate. I don’t think it’s a bad thing to wish people would look critically at their beliefs and discard the ones that no longer work with modern understandings of history and morality.

self-deleted

Comment I was replying to was deleted by mods.

Stepping in with a reminder to please keep things civil and avoid being overly aggressive and/or dismissive, especially when discussing religions, beliefs, and philosophies that may be separate from your own. Since this discussion seems to be getting a bit heated, I’d suggest that everyone keep our community standards in mind, as outlined in the Moderation Policy. Thanks.

Re: human religion on Star Trek, I always thought the implication was not that everyone was atheist in the future, but that people had their own religious convictions that they didn’t let interfere with their relationships towards others that held different beliefs. There are little clues here and there, from the nearly overt (Riker talking about interfering with a “cosmic plan” to be the “height of hubris” in the episode “Pen Pals” seems an awful lot like he’s drawing upon a belief in a Creator to justify his thought process, even if he doesn’t explicitly state it) to the could-be-religious-could-be-cultural (Christmas celebrations, Keiko’s Shinto wedding garb, Bashir and O’Brien singing “Jerusalem”, etc.). I’m just afraid that a Trekkian commentary on faith might skew a little more towards Star Trek V territory than anything useful.

So where is George Takei in that pic?

I don’t think human religion should be introduced to Star Trek at this point. Whether you agree with the premise or not, it’s been made pretty clear that Star Trek is a post-religion humanity and introducing it at this point is changing what makes Star Trek Star Trek. It’s based on Gene Rodenberry’s vision of the future and he envisioned it without religion.

Not to mention that the topic is a minefield. Look at how much (for example) Christianity has changed in the last 400 years. It will, of course, be as different – if not more so – in 400 years time. Try to accurately represent a radically (and realistically) changed religion and you’ll be lambasted. Show Christianity as essentially unchanged 400 years into the future and it will be laughable.

Long story short: It doesn’t fit and it’s a topic best avoided anyway.

My take on religion among humanity in the Star Trek universe is that many humans are spiritual, both by culture and inclination. We see an example of this in Chakotay‘s Native American rituals. Organized religion is basically gone because:

1. There is no money to be made or taxes to evade. Yeah, it’s cynical, but a lot of religions today wouldn’t exist without this motivation.

2. Emergency services and resources are instantaneously available. Many people dedicate their lives to helping others without any religious motivation and there is no need for most charitable services as we know them today.

3. Parents aren’t so concerned about instilling morality in their children because there are much more fun and interesting holosuite moral adventures and such to psychologically program the kids.

4. There are still people who dedicate themselves to teaching about their faith and passing on their spirituality, but they have been psychologically programmed and socially conditioned to not be pushy. It’s not a career.

5. Political motivations for certain religions are gone. There is also the legacy of the Eugenics wars which certainly had religious undertones. People are desperate not to repeat this. There are also probably different laws about organizing religions.

We don’t see a lot of ordinary, non-Starfleet life on Earth, but in what we do see there is plenty of evidence for normal human superstition, which is part of our nature, and cultural remnants of religion. Most humans seem to be accepting and even willing to participate in the alien faiths they come across.

I would like to see a devout Jew on Star Trek. That is a religion that has a unique culture and code of conduct which I imagine could survive intact, and it would be interesting to explore how this character would interact with aliens and other humans in the Federation.

Dealing with human religions in Star Trek might sound cool on paper, but it is a very tricky thing to do correctly.

The best way to get the IDIC ideals across is by simply having a diverse crew who are doing their professional jobs. The simple presence of people like Uhura and Sulu and Chekov on the bridge of the Enterprise, gets the message across far more efficiently than any specific morality story that Trek ever made.

Now here’s the problem:

Doing the same thing with religion is very very difficult. Religion is a world-view which affects everything the person does. Having a crewmemeber with a cross around their necks without it having any further consequences would just look foolish. On the other hand, trying something more substantial will probably give too much attention to something which should “just be there”.

So in order for this not to end in a complete disaster, the writers would need to walk a very fine line. A line so fine that very few people would be able to pull such a thing off.

@38/OmicronThetaDeltaPhi: “The best way to get the IDIC ideals across is by simply having a diverse crew who are doing their professional jobs.” – I agree.

But I think it could be done and wouldn’t be too tricky. They did well with Chakotay, apart from the fact that he was a generic Hollywood Indian. Another example: In Diane Duane’s The Wounded Sky there’s a scene where Kirk does a spacewalk and prays before taking a difficult decision. Now, I’ve seen the claim that Kirk wasn’t a religious person in the TV show, so maybe that was out of character, but it worked fine as a part of the main character’s decision-making process.

So sad to see so people who are Star Trek fans have only negative views about religion or are dismissive of representation of sexual/racial diversity onscreen…

@3 – Halien:

“I don’t want the show to become overly concerned with the personal lives or identity issues of the characters.”

That’s funny, because a lot of us do want that. :) We don’t want a show with interchangeable crewmembers visiting a planet one week and never going back, like most of TNG. I want them to be stuck with the problems they deal with, and I want to see a lot of their personal lives and identities, like DS9.

@36 – rfresa:

“We don’t see a lot of ordinary, non-Starfleet life on Earth”

I wish we did.

@39/JanaJansen “But I think it could be done and wouldn’t be too tricky. They did well with Chakotay, apart from the fact that he was a generic Hollywood Indian.”

Yeah, but Chakotay’s culture was made up on the spot, so the writers could pretty much do whatever they pleased with it.

Doing the same thing with an actual religion/culture would be much more difficult. The writers will have to have a very deep understanding of what they’re trying to portray, or it will likely end up as an unintentional mockery.

“Another example: In Diane Duane’s The Wounded Sky there’s a scene where Kirk does a spacewalk and prays before taking a difficult decision.”

I think this kind of things are much easier to do in a one-time-off book than on a TV series which requires over-arching consistency and contininuity.

It isn’t out-of-character for Kirk, though. There’s the line from “Who Mourns for Adonais” where he said “Mankind has no need for ‘gods’. We find the one quite adequate”. So apparently Kirk is some kind of monotheist (or at the very least a deist).

And I absolutely love this line. It is so subtle yet so direct. It might even be taken to mean that in the 23rd century the differences between religions would cease to matter, since they all acknowlege the very same “one”… But there other possible interpertations which is exactly what makes that line so perfect.

At any rate, this scene from TOS, just like the scene you’ve mentioned from The Wounded Sky, works precisely because it is isolated. Trying to do this on a regular basis would require narrowing down the possible interpertations, which opens a whole new can of worms (see Irrevenant’s comment #34 on the pitfalls of extrapolating actual religions centuries into the future).

Personally, I would really like to see something like this being pulled off in a decent manner. I’m just not very optimistic about the odds of such an attempt ending well. I’ll be happy to be surprised, though!

@40/MaGnUs: I agree 100% with everything you said.

@41/OmicronThetaDeltaPhi: Actually, I agree with you about Kirk. It didn’t seem out of character to me either. I added that line because it seems to be a controversial subject (Do you remember the discussion in the Who Mourns For Adonais? rewatch?), and it wasn’t my main point anyway.

“Doing the same thing with an actual religion/culture would be much more difficult. The writers will have to have a very deep understanding of what they’re trying to portray, or it will likely end up as an unintentional mockery.”

They could pick religions they do know something about. Or employ advisors. I think it would work best if they limited themselves to small scenes and symbols in the background of the stories. But I know what you mean, it can easily go wrong. It requires a nuanced portrayal, and nuanced portrayals probably aren’t Nicholas Meyer’s strong suit. I don’t know the other writers, though, so I like to imagine that they would be up to it.

But what if there is more to us than that?

Well, of course not. At least, one can always hope, right? Which begs the question: what more is there in all of us, buried like some unknown treasure? And how can we go about unearthing these inherent qualities? If we can answer these questions, and proceed to live a life according to our values, with open-mindedness and respect, then I believe there could be a bright future for humanity. Which, in turn, begs another question: is all of this naive thinking? Is it idealistic? Maybe, maybe not.